by Kayla DeHoniesto, 2019 Jackson Center Summer Fellow

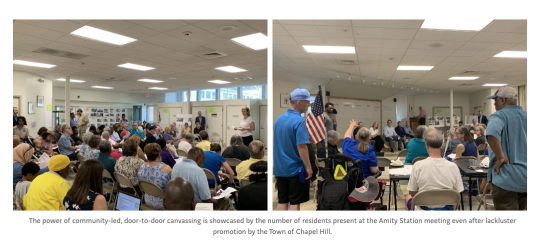

As I walked out of the Amity Station Community Meeting, on my second day of this fellowship, I could not process the thoughts and emotions running through my head. I could sense anger, frustration, guilt, heartache, and excitement all in one. Each emotion fought for prominence in my brain, but I ultimately walked away from that meeting confused; confused on what there was left to do and what my personal role was in this new community I had adopted. But in order for me to understand my role in fighting the gentrification affecting Northside, I had to first understand what the neighborhood means to me and to its residents.

I have lived in predominantly white neighborhoods and operated in predominantly white spaces my entire life. The last true Black community I belonged to was Girl Scouts and my church, but both of those communities were cut from my life when I moved states. I bring this up not to give reason to why I don’t feel connected to Black spaces because every day I bask in the glory of my Blackness. However, I think the lack of a community of people who not only look like me but can provide comfort when navigating the realities of being Black in America have left me longing for a particular type of connection. I have never felt connected to elders who lived through the struggles for freedom that afforded me with the privileges I have today. But Northside is different from any community I have ever known because the connection between residents is infectious and special, vibrant and established. When you meet the people of Northside, you meet people who immediately feel like family, and a neighborhood that is so connected it almost feels like the textbook definition of what community should mean.

This legacy of community does not exist in a vacuum, and it is not purely a side effect of Blackness. Northside remains united because of the common experience of struggle, the historic spirit of fighting for civil rights, and the power of collective memory that keeps people together. And it is the spirit of that connection that makes its slow disintegration that much more tragic. The growth of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the city around it has created a major development boom in the town, especially in regards to student housing. Northside, which has been historically Black and low-income, has become a hub for developers and investors to create new student rentals, thus changing the demographics of the neighborhood while also hiking up the property taxes for long-term residents. Thus, the lifetime residents of Northside who created its thriving culture have been systematically pushed out not just by the rising costs of living but by the loss of a sense of community in their neighborhood. I have talked to residents who have seen almost every house on their street transformed into expensive student housing, thus pushing out families who want to live in Northside and erasing the close-knit community that made Northside a safe haven for Black families for decades.

This is gentrification at its finest.

The Oxford dictionary defines gentrification as “the process of renovating and improving a house or district so that it conforms to middle-class taste.” There is nothing inherently wrong with a natural change that takes place over time, especially within a community Northside, which has been around for decades, since well before the Civil Rights Movement. But when the so-called “improvement” in the neighborhood only benefits profit-driven developers and oblivious students who aren’t aware of any communities outside of campus, the residents who make up the backbone of Northside become an afterthought. The histories, legacies, and culture of what was a vibrant beacon of Black life in Chapel Hill have been decimated by the expansion of a university that boasts development and innovation while simultaneously erasing the legacy of the families that built it.

As a student, I feel torn. On one hand, Northside provides so many of my friends more affordable housing than on-campus dorms and fancy apartment complexes, so I understand the desire to live there. But as an activist and a fellow of the Jackson Center, I am witnessing firsthand the devastation that student rentals cause for this community. I struggle to find a middle ground between supporting long-term residents of Northside who have provided me with so much wisdom and compassion, while also knowing that many of my friends would struggle to pay rent in other neighborhoods. At what point do I stop being a student and begin advocating for this community? Are they separate roles? Can I ever truly fight the gentrification of Northside while continuing to go to parties and visiting friends in Northside?

I think one of the hardest parts of activism, or just being a citizen who is aware of the injustices around me, is not knowing how much impact I can really ever have. I wonder about how much power I have against the powerful tides of gentrification, and how does my role as a student play into understanding and connecting to the community around my institution. I also struggle to decide how much students are at fault for giving in to the greedy operations of developers who seek profit above humanity. Is it more effective to place the blame on developers, students, or both? Sometimes the impact and change I would like to make in the world around me seems too big for a tiny person like me to manage.

For me, I think this work starts with just learning who my neighbors are and what Northside means to them. I think we can look to Northside, where justice and activism flow through the blood of almost every long-term resident, as an example of what community-based activism can accomplish when everyone is invested in the fight against gentrification.

-Kayla DeHoniesto

Leave a Reply