“The conversations were great and I think that’s where I got my knowing there’s two sides to every story. And I’ve carried that up through my kids and my grandkids.”

– David Caldwell, Jr., June 9, 2017

Over the course of the last few weeks, I have spent time getting to know a man whose family seems to represent what it has meant to be black in Chapel Hill over time.

David Caldwell, Jr., is, at about six and a half feet, an imposing figure with a warm smile and easy laugh. Since the founding of UNC, the Caldwell family has lived here, the white Caldwells and the black Caldwells bound together through the institution of slavery. One family owned much of the land on which UNC’s sprawling main campus now sits.

After the Civil War, many of the newly-emancipated Caldwells stayed on to serve UNC presidents, as well as its fraternity boys and professors. These Caldwells moved to the surrounding area and many ended up, along with other descendants of slaves, building houses in the Northside neighborhood in segregated Chapel Hill.

My interviews with David began with a few photographs.

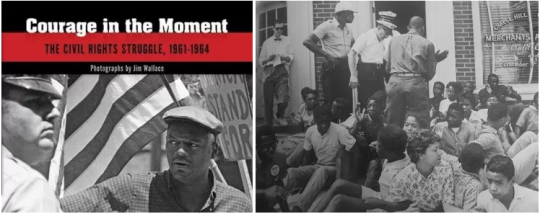

The cover of Jim Wallace’s Courage in the Moment, a series of black and white photos from the civil rights movement in Chapel Hill in the early sixties, features a tall black man leading a protest march past a white police officer. Other pictures in the book feature another tall black man, a police officer on the scene to patrol the protests.

It turns out, these men were brothers.

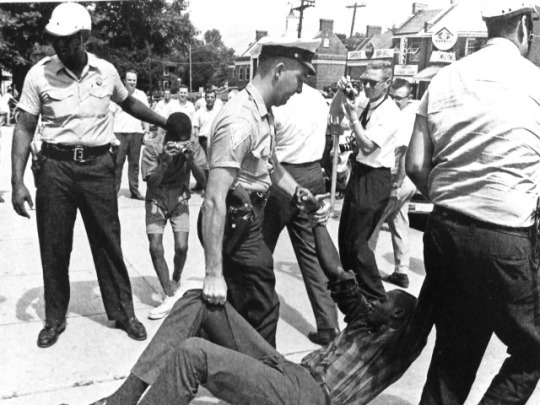

One of them was David Caldwell, Sr., one of the first black policemen in Chapel Hill. In this photo, he’s the police officer on the left.

The other was David’s uncle Hilliard who is widely credited with organizing many of Chapel Hill’s civil rights marches and smoothing the way to integration at Chapel Hill High. In the photo below, he’s wearing his trademark cap, holding the left end of the banner.

How could you not want to know what Caldwell get-togethers in the 1960s were like?

DC: It always made things very interesting for family gatherings …with my father being on one side and Hill on the other. And I don’t think you’ll see my father arresting anyone in these pictures but he was there as far as helping people. The comment was made that when he had one of them, that he only stood up against the wall and did not participate …

AW: How did he get away with that?

DC: He just didn’t do it. … He showed up and did everything but what they’re doing.

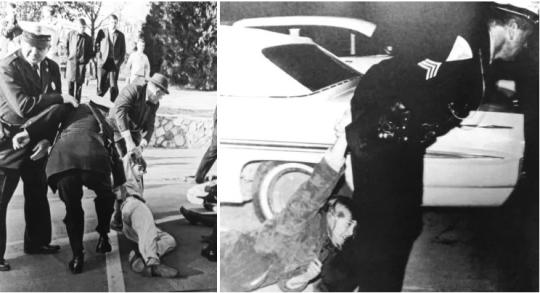

[Note: He is referring to some of the forceful arrests of demonstrators, like these captured by Jim Wallace below]:

David Caldwell, Sr. did not have to pull out a baton or drag a demonstrator into a paddy wagon, though he did assist with carrying some. He was a presence– watching, but also watching out.

And he was being watched, tested by his fellow officers. His self-respect was on the line whenever he went to work, and his dignity had to be sacrificed more than once. In David’s words, “Dignity was good but it didn’t put food on the table. So you had to do a lot. You had to eat a lot of straw to just make sure things didn’t go wrong.” For David and his three brothers, that meant not getting involved in marches, demonstrations or riots.

His father’s influence, however, did get David out of a few difficult situations, usually when he was in the wrong place at the wrong time. Like the time he and his buddies were crossing campus after dark when the police were answering a sexual assault call. Or the time David was pulled into a student demonstration at Chapel Hill High and was handed a rock to hold. On these occasions, David felt the relief that came from his father’s hard-earned respect in the community. Once police recognized “Big Dave’s” son, they eased up on him. But David Jr. knew he wasn’t off the hook just because the cops stopped questioning him. He feared the very thought of coming home and having to answer to his dad.

So, what really happened at those Caldwell family gatherings?

Here’s how David tells it:

You just kind of sat back and listened to their discussions. And they would talk about things that weren’t right and things that weren’t done and … they always been a hard working group. They all had 2,3 jobs at one time. And to talk about things they would, you could hear them go through on their jobs, was just amazing to me, to listen and say, okay so this is—I didn’t know what it was called then. I knew it wasn’t right. … It was racism.

He told me stories about how his father took him to black law enforcement officers conventions where he heard countless stories of injustices they suffered on the job.He saw his father address young white men with “Sir.” But he also told me about how, later on when his father owned a garbage collection business, he would pay for his trucks in cash, stunning the condescending white salespeople who assumed they would need to work out a considerable loan. These were the small triumphs, but they clearly made an impression on David.

And he told me about how Hilliard, who worked as a truant officer, faced similar challenges and dangers. Hilliard realized that truancy was often linked to poverty. He made house calls and found that kids often stayed home because they didn’t have a shirt, shoes or money for lunch. I had heard that in the early seventies, Hilliard had been a sort of liaison between protesting students and resistant faculty at newly integrated Chapel Hill High, and so I assumed he had somehow earned the trust of both sides. As David put it:

I’m not going to say that that administration had any trust in him. This is my opinion. Because it was, the people that were there were put there because they had to be put there. They didn’t want them. I’d be surprised if you could find anybody there that could say, ‘This administration wanted us there.’

And so David’s social studies and civics lessons were often learned by listening to the older generation talk. One thing he learned is that no matter where they worked, they always had stories of prejudice, discrimination, and frustration due to the inability to retaliate.

Initially, when I asked about the differences between his father and his uncle’s response to the civil rights movement, David’s answer surprised me:

It didn’t affect the chemistry of the family at all. I mean, it was just like sitting down and talking about football. It did not affect anything. We just, you know, sat and listened and learned. It made it easier for us to identify, to think on our feet when things were going down.

And things were definitely going down. The pictures featuring his father and uncle were taken during the demonstrations, protest marches, and sit-ins of the early 1960s. When the voting rights act was passed in 1964, Chapel Hill was unaffected at first. It took four years before protests began again, this time in response to the town’s feet-dragging on integration mandates. Here David describes his experiences with race at the time:

The town was very divided. I loved growing up and seeing so many black people. It was unbelievable up on Graham Street and Merritt Mill Road and the black businesses and the black theater, black stores. You know it was just a huge deal. And you had a line that you didn’t cross, that was understood. We had a time limit that when that time came you needed to be back on that side of town. And I was just young but I was old enough to see it and recognize it, that something wasn’t right.

Prior to actual integration, David was one of the first black students to enroll in all-white Phillips Middle School. At Phillips he was forced to apply strategies he picked up from those dinner table conversations.

I went to Guy B. Phillips. And seeing and dealing with teachers who didn’t want to teach you, students that didn’t want you there. ( ) I remember going and feeling like so many times, you know, ‘God, what did I do wrong? … Why are they making me go here and making me go through this every day?’ And you know, it was almost like, you know, we have to pay this bill. And this is how you pay it, for everybody to benefit from it. I remember being hit in the back of the head, pushed down the steps. Teacher asked me one time, that, what I was fighting for? And I said, ‘Well, he pushed me. He called be a nigger and pushed me down the steps.’ He said, ‘Well, son, you are a nigger.’

So, David was faced with the same sort of situations his dad and uncle described around the dinner table. The lessons he learned from both David, Sr., and from Hilliard were more than the lessons he could have learned from each one of them alone. The whole was more than the sum of these two parts.

David learned about different ways to get along in segregated, deeply prejudiced, hostile and sometimes violent Chapel Hill, different strategies for the daily fight. But he also learned to listen to all sides before making a decision, that there is something to learn by considering different viewpoints. And looking back over his rich life so far, it’s possible to see the influence of father and uncle: he has served his town and his country and he’s been a tireless activist for social and environmental justice in his Rogers Road neighborhood.

David Sr. and Hilliard faced enormous obstacles and suffered countless humiliations, but they also talked to each other. Each could understand what the other faced, and they shared their stories, leaving David and the other young Caldwells to make their own decisions. The young David must have realized that his elders were able to make inroads and bring about change one step at a time. He had to be patient but not joining the struggle was not an option.

He learned the value of listening, maintaining respect for those with different views but with common goals. As the younger Caldwells faced prejudice and discrimination in their white-majority schools and town, they knew they were often, as David puts it, “up against an army.” But not without an arsenal of family-tested survival strategies.

One of the many things I learned from David is how to make better sense of the pictures of the time. He has shown me how to read the pictures in which I used to see police vs. protestors. In those pictures, his father is not just playing the part of the cop; he is fighting his own battle for respect, for a decent income, for his family and community. And Hilliard, as a truant officer in the schools, also faced off daily with those who did not want him or the kids he cared about to be there. Even as the conflict played out on the streets, the family held together.

Though the photos depict two sides at great odds with each other, what one cannot see is that the Caldwells had much more that held them together, more that they agreed on than disagreed on. Compared to the crippling weight of racism, a difference in political strategies was not a deal breaker by any stretch. They still shared the same side of town, the same neighborhood, the same day-to-day racism. … and a bond that has spanned generations.

Leave a Reply