By Andrea Wuerth, Reposted from April 30, 2017

I’ve often walked from Franklin Street to Rosemary Street, down Roberson or Church or Graham Street and never realized I was crossing a former color line.

There are no obvious markers, just a few remnants of what used to be the Black business district on Rosemary, where the Northside neighborhood begins.

There’s First Baptist church, St. Joseph’s AME and its parsonage (now the Marian Cheek Jackson Center for Saving and Making History). They all were centers of Northside life during the long era of segregation, when these churches, though open to all, were attended only by black residents of Chapel Hill.

When I was teaching at East Chapel Hill High, I was not aware of any classes in which students learned about segregation right here at home. The Jackson Center’s staff has developed numerous educational programs in which Northside residents come to classrooms and tell their stories.

This past week, representatives of the Jackson Center and the Northside neighborhood visited the new Northside Elementary school to tell some stories. The fifth grade classes, which had been learning about oral history and the history of the neighborhood, assembled in the library to ask the questions they had prepared for their guests.

One question after the other focused on the chapter of Chapel Hill history that many residents have chosen to forget, the daily reality of segregation and Jim Crow:

- When did you realize there was segregation?

- How did segregation have an effect on you and your family?

- Were there some times you got mad or frustrated about segregation?

- How do you feel about segregated churches?

- Give an example of a time you saw a white person stand up against segregation.

- How did you feel when you had to change schools?

- How did you feel going into an all white school?

Like these astute young oral historians, I also want to know the answers to these questions.

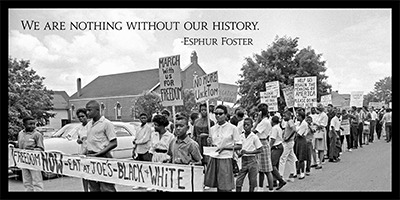

The Northside panelists responded with stories about being warned not to go to “white” areas of town, including Franklin Street and the University campus. They described enduring insults; being turned away from public places; sitting in classrooms in Blacks-only schools with furniture and textbooks handed down from “white schools”; pushing themselves to succeed in integrated schools. And they recalled when white kids invited them to go places and they had to tell them “no, they couldn’t” because their parents didn’t think it safe. They described the courage it took to take to the Chapel Hill streets in the early 1960s when they faced arrest, hateful remarks, and physical violence. And they also talked about the support and safety of their community and the empowerment they felt in neighborhood homes and churches.

Just a few examples:

Stan Foushee said he was used to lots of freedom in his own neighborhood but was introduced to segregation when his parents told him there were certain places we could not go. “If we said that we were going downtown CH, they would say, no, you can’t go downtown CH. You definitely couldn’t go to the university, stay away from the frat houses and those sort of things…”

Pat Jackson tells the story of being invited by white friends to go roller skating at the Presbyterian Church during segregation. When they arrived “bureaucracy and politics got in the mix,” and the black children were told they couldn’t go into the church roller skating rink. She explained that the kids (both black and white) asked why they couldn’t enter. And it was because “adults had made the decision that because of the color of your skin, you can’t go and skate with your friends. … Can you imagine how we felt?”

Clayton Weaver was a student at Lincoln HS (all black) in 1964. He explained that some black students were given the choice of going to the all-white Chapel Hill High School. He and 13 others did. His reason: he was top of his class and he thought, “Let me go down the street here and see what I can do.” But “it was a whole different world. There were trials and tribulations I never thought I’d have to deal with.” Last week he told the kids he was still glad he went because it taught him what he’d have to deal with after high school. But many of his black classmates look back with regret about that decision: “There are still scars today.”

Pat Jackson

This long and dark chapter of Chapel Hill history looms over the present here. It’s so easy to ignore since there are so few signs pointing to it. These questions remind us that we should not be trying to cover it up; we should be planting signs that lead to it.

And the search for the answers to their questions will lead to some difficult discoveries and challenging conversations. Conversations that have been cleverly avoided and are long-overdue.

Our kids today are asking the questions we all have to ask if we want to heal our town’s racial divisions. I’m certain that without this look at our past, we will be taking a step or two back every time we take a step forward.

By asking their questions, these fifth graders are about to unearth the past in the way Marian Cheek Jackson would have wanted them to when she said, “Without the past, we have no future.”

Kids, you honor the memory of the great lady of Northside. She would have been very proud! Go and find the answers. And know that you will be making history in the process.

Andrea Wuerth is a volunteer participant in the Center’s Learning Across Generations local history curriculum and our Oral History Archive. She agreed to let us post her blog entry after archiving Hollywood’s oral history interview. Access to Andrea’s full blog can be found here.

Leave a Reply