By Heidi Dodson

Heidi Dodson is the Oral History Scholar-in-Residence at the Jackson Center.

If you come across the railroad track, you’re going to run into Brewer Lane. And when you get there from Brewer Lane, and you come on around the curve, right there is Hargraves Street. That was Tin Top. That little area was up there, Tin Top.

–Donny Lee “Hollywood” Riggsbee (May 9, 2012)

For much of this year I have been privileged to listen to and read the stories people have shared about Northside, Pine Knolls, and Tin Top. I’ve only lived in Chapel Hill-Carrboro for five years, and I love learning the history of its neighborhoods. How can you call a place home without getting to know its past? Hollywood Riggsbee is one of the people I have learned from, and his description of Tin Top captured my imagination.

“A while back, back, I’d say, twenty, thirty years ago, we had some old regular houses with tin on them. They was in a row, lined up on Hargraves Street. That’s where it was called Tin Top because it had tin on the houses. I mean, it was, everybody knew each other…the whole top row, up on Hargraves Street….everybody up there was some kin. Except my aunt, she stayed right there in the first house but she didn’t have no tin on her house. She had a regular roof on hers. We was in the bottom. The top was called Tin Top, the top part. And we was in the bottom. We was Carr Court.”

(May 9, 2012)

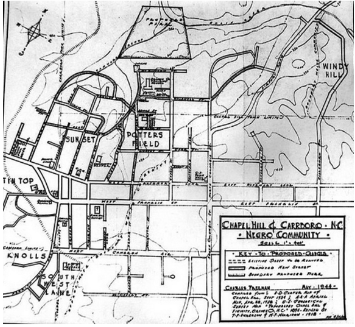

Freeman, Charles M. Chapel Hill & Carrboro N.C.: Negro community. 1944. Original in the North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina.

Hollywood’s description stuck with me because it evoked the sound of rain pounding down on the tin roofs, drowning out the sound of everything else inside the houses. His memories brought to mind an interview I did in rural Missouri with Eugene Speller, who grew up in a sharecropping family. I had never given much thought to roofs: their construction, what they were made of, what they cost, how they sound, and how they might affect daily life. Eugene’s family moved to a place where they had to build their own house. They didn’t have much money, so they scouted around a nearby town for materials. He prayed they would not have enough money to get the tin.

“You know what it’s like in the rain with a tin roof? It’s worse than the wood owls. But when it rains on a tin roof…it’s terrible.”[1]

I thought about Tin Top – what did it sound like on Hargraves Street when it rained? Was it only loud inside the houses? Could family and friends talk to each other above the noise? Was it difficult to go to sleep or was it something one grew accustomed to, like the sound of a freight train? Did the tin roofs keep the rain out?

We often take the sounds around us for granted. This is also true when we study the past. We ask questions about who, what, when, and where. We try to understand what people were feeling and seeing, and we look at maps and photographs to visually understand a place. We neglect sounds, even though they are interwoven with the physical landscape and change over time. Today, if we live in a city, we get accustomed to the sound of traffic: horns honked in agitation, the urgency of sirens, the smooth whoosh of tires on the road. In the country, we might be more familiar with the crunch of tires on gravel or the chorus of frogs. How are the sounds and sights today in Northside or Tin Top different from they were fifty or sixty years ago?

Hollywood’s recollections of Tin Top and the sense of community and family they revealed inspired me to learn more about the neighborhood. I found an article online about Orange County places. Using land records, maps and books, the author (unidentified) provides a fascinating spatial history of Tin Top. However, the articles starts by saying the neighborhood “came into being in the 1920s, but was gone by the 1940s.”

I was surprised to read that. Hollywood grew up in Tin Top in the 1960s so I knew it was not gone, even if the name was no longer inscribed on a map. The idea that Tin Top has disappeared speaks to issues of authority and naming. Who gets to name a neighborhood? How do we know when it begins and ends? Although town officials or developers may assign a new name, residents carry their own neighborhood identity into the future through the telling and retelling of their history.

The tin top houses that Hollywood described on Hargraves Street were built in the 1920s by Luther R. Hargraves, a carpenter and the first African American mortician in Chapel Hill. Mr. Hargraves was the grandfather of Velma Perry and Janie Alston. Here are some of their memories, recorded in oral history interviews:

Janie Alston: My grandfather would build houses for people, and bury people. And people that didn’t have money: he was a Christian man, so if people didn’t have money, he would still bury them. And they would give him a hog or some chickens. He needed to feed his family, so he just, you know. And he would build houses and he wasn’t a very good bookkeeper, because he would just take people at their word and people would pay him and people would not pay him. Like where Tin Top is now? He built those houses. You see that street that says Hargraves? He built houses with tin tops down there. And some people paid him, some didn’t. But then when the Depression came, he lost a lot of stuff.

At that time I guess that’s what they did, put tin tops on the houses. I wouldn’t want to live in a house with a tin top, it makes too much noise. A lot of people like that sound.

Daphne Attas, author of the memoir Chapel Hill in Plain Sight, lived near Tin Top in the late 1930s when she was a child. She recalled that “In the South there were usually two towns, the white and colored. These towns defied their descriptions, because the white town’s houses were painted in colors and the colored town’s houses were never painted at all, and were colored by weather, no color at all, just weather-changing color.” The Attas family lived in the “colored section.” The house they rented was old and long past its prime. It was located “on a knoll off Merritt Mill Road in the shade of three butternuts and three oaks, separated from the colored town [Tin Top] by a four-acre field of broom grass.” It was also near the train tracks. An African American woman named Mrs. Snipes “ran a one-room store at the edge of the tracks.” As the season turned from summer to fall and the trees shed their leaves, Attas and her family could see “the shambles of tin roofs against the honeysuckled dirt.”

The Attas family called their house the “Shack,” and Daphne believed “the type of houses people live in do the dictating.” She describes what her house communicated to her about the tin roof: “I have an old tin roof upon which no cats can run, only squirrels and chipmunks. I dictate the seasons of the year when nuts fall down on my tin roof. They report like pistol shot.”

Rain, music, laughter, wind, acorns, freight trains – the quick pitter-patter of mammal feet on what in the summer was a hot tin roof; they were all part of the part of the soundscape of Tin Top and other neighborhoods that used metal roof to keep out the elements.

Luther Hargraves’s carpentry and housing construction also would have created new sounds that signaled community growth and prosperity: hammers pounding nails into tin roofs, the voices of workers calling out to each other.

Hudson Vaughan: How did he [Luther] get into building, do you know? Do you know how he began to—?

Janie Alston: No, I don’t. I don’t know why he became a carpenter. I don’t know if Jerry [his father] was a carpenter before.

Jerry Hargraves was a carpenter. Born into slavery ca. 1835, he would have been about thirty years old when the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified, ending slavery. He and his wife Martha (nee Oldham) started their family before the Civil War ended, and Luther was born in 1869.

Velma Perry: Great-grandad was a carpenter and so was grandaddy. He helped build houses all over the place. It was Tin Top they called it. You know where my church is? [St. Paul AME] Behind my church, that was, they call it Carrboro now…that was all his property. All that property was my great-grandaddy’s. He built thirteen houses down in that area. And he put tin tops on it. And the neighbors and the people in the town named it Tin Top Alley. They wasn’t big houses, little houses, three or four rooms or something like that.

Jerry Hargraves was also one of the original founders of St. Paul AME Church, which was organized in 1864. As a carpenter, he probably used his skills to build the church structure in 1892.

After researching her family history, Ms. Perry was surprised to discover her grandfather could read, write, and count, given the lack of educational opportunities for African Americans in Chapel Hill. But it is possible that Luther attended school for a while. In 1880, two of his older brothers were attending school. In the years between the Civil War and the turn of the twentieth century, African Americans were very involved in educating children in Orange County. One of those teachers was Wilson Swain Caldwell, who had worked as a janitor at UNC. He took over a “free school for colored children” located on the corner of Cameron Avenue and Mallett Street.[2] Carrie Jones moved to Chapel Hill from New York as the servant of a university professor. After a few years, she started teaching in Alamance, Orange, and Chatham counties in schools run by the American Missionary Association. Then she started her own school, which she named Hannah Lowe after her mother.[3] Pauli Murray’s grandfather, Robert Fitzgerald, taught school through the Quakers, for the Orange County school board, and ultimately started his own free private school in Chapel Hill.[4]

Hargraves was an enterprising businessman. In 1920, the Durham Morning Herald reported that he, along with Luther Edwards, L. H. Hackney, Van Nunn, Durwood O’Kelly, Ernest Thompson and B. F. Hopkins, were granted a charter for the Progressive Manufacturing Company in Chapel Hill. It was for the “manufacture and sale of brick and clay products,” and had authorized capital in the amount of $50,000. Rev. Hackney was the board president. The 1920s were a time of expansion and growth in Chapel Hill and the African American community, which included the Black business district on the west end of Franklin.[5]

In April 1923, the Chapel Hill Weekly noted that Luther Hargraves “has become a capitalist and put up four dwelling houses out on the street that runs north from the Baptist church. Three of them have already been let and are being lived in and the fourth will be occupied soon.”[6]

Unfortunately, just two months later, in June of 1923, Hargraves and his wife Della had a financial setback. Someone accidentally set fire to their barn, destroying a hearse and killing a cow and horse. "The total loss suffered by the carpenter-undertaker is estimated at from $800 to $1000. There was no hydrant near enough to permit Fire Chief Foister and his men to train their hose on the barn.“[7] At that time, the municipal water system in Chapel Hill was still in development. The University supplied water to the town and expected to extend a pipe down Franklin Street to the west end by early December. Yet the Weekly explained to readers that "no progress has been made in the last few months in the scheme to extend a pipe line from Franklin Street along Church Street to the colored folks’ section known as Pottersfield.”[8]

Although the barn fire was a devastating loss, Luther Hargraves’s excellent reputation in Chapel Hill prompted assistance from others. In June, the Weekly alerted readers that “Luther Hargrave the negro carpenter so well known to the citizens of Chapel Hill, had a severe financial blow when his barn burned up recently.” Donations were encouraged.[9] The family recovered, and Luther continued to operate the funeral business and construct new “tin top” houses in the Black community throughout the 1920s.

[1]: Eugene Speller, interview by Heidi Dodson, June 11, 2012, interview

U-0856, Southern Oral History Program Collection #4007, Southern Historical

Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. [2]: John K. Chapman (Yonni). “Second Generation: Black Youth and the Origins

of the Civil Rights Movement in Chapel Hill, N.C., 1937-1963.” Master’s thesis,

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1995. [3]:

“Carrie Jones Has Taught 40 Years,” Chapel

Hill Weekly, March 22, 1923.

Rosetta Austin Moore, The Impact of Slavery on the Education on Blacks

in Orange County, North Carolina, 1619-1970 (Lulu Publishing Services, 2015),

36.

“New Enterprises,” Durham Morning

Herald, February 21, 1920.

Untitled, Chapel Hill Weekly,

April 5, 1923; “Industry,” The Crisis,

November, 1920, 80.

“Horse and Cow Burn,” Chapel Hill

Weekly, June 12, 1923.

“Colored People Hope for Water,” Chapel

Hill Weekly, August 9, 1923; “Water Service for West End,” Chapel Hill Weekly, November 8, 1923.

“Luther in Trouble,” Chapel Hill

Weekly, July 5, 1923.

Leave a Reply